This post is going to deal with calculating the return on investment for click-based advertising – Facebook, Google, Amazon, etc.

One of the assumptions I’ll make here is that you have more than one book in a series before you think about advertising. If you only have one or two books out, your best ROI is going to be time spent writing the next book. Nothing advertises your old books as much as a new book on the New Releases Best Seller list. Go write something … which is advice I should take myself right now, but here we are.

Anyway, the first thing you need to do to start calculating ROI on ads is to know what you’re selling — and that isn’t just the book you’re advertising. You’re selling your entire series, so you need to know the value, on a series basis, of a new reader. To do that, you first have to determine what your read-through percentage is.

That’s the number of readers who move on to book two in your series after they buy book one — and on to book two, three, four, etc.

This is best done with a large dataset, such as all your sales for the last year. If you ever ran a lot of free sales, that data will skew your numbers, so adjust for those. Frequent $0.99 sales or just changing the price up and down will also skew read through — your $4.99 buyer is a better qualified lead because they’ve committed more to the initial transaction than a $0.99 “I’ll pick it up and maybe read it sometime” fellow. Once you have several years of data, it’ll average out, but this is something to consider if your releases are relatively new.

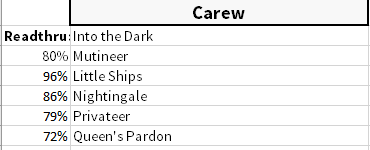

In my case, for my Carew series, the sell-through looks like this:

80% of Into the Dark readers buy Mutineer, 96% of those move on to Little Ships, etc.

These numbers are naturally going to drop from book to book and the more time you have between releases the more they’re going to drop. Readers will get bored with your work, forget about you between releases, move on to other interests, die, go to prison, etc.

The next step is to figure out the average value a new reader brings to your series.

So in my case, if a thousand new readers buy Into the Dark at $4.99, I’ll earn $3493 in royalties from Amazon. Eighty percent, or 800, of those thousand will move on to Mutineer – for $2794.40 in royalties; and 96% of those 800, or 768, will buy Little Ships for $2682.62 in royalties, etc.

By the end of the series, with some readers dropping off at every step, I should have collected $14,411.91 from those 1000 readers who started — thank you, by the way. I hope you enjoyed the stories. 🙂 And, yes, I’m working on the next book — slowly, but working.

The average value of a new reader, for me, is $14.41.

Fewer books means fewer levels of read-through, so, again, the more books you have out, the higher monetary value each new reader has.

This is where authors differ from other businesses when it comes to ads. If I’m selling widgets, then my customer is likely to buy one widget and be done with me. Maybe there’s repeat business, but, in general, I sold my widget.

For an author, the sale is the series, not the single advertised book.

You might disagree with this and want to calculate your ROI on just the first book in your series — that’s cool. Everybody has their own criteria. For me, I want to sell someone all six books, not just the one, so that’s how I calculate it. The ROI might take time, maybe months, to fully come in, but that’s my game.

The next inputs to find are the cost per 1000 impressions (CPM), the click-through rate of the ad (CTR), and the conversion rate (how many people who clicked, then bought (book one).

These you have to get from testing the ads themselves, and the conversion rate is the hardest bit of data for authors to get.

Facebook, for instance, will tell you the first two, but it can’t tell you the last one. And Amazon won’t tell you. It would be really nice if they’d let you send a parameter into Amazon that showed up on your reports, but they don’t. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

So we have to … guess. You take the baseline average sales from before your ads start, then your average sales after they’ve been running for a few weeks, and that’s your conversion rate. Typically you’d run this data gathering process at a low ad spend — which, unfortunately, means the number are going be low and not stand out. If you’re averaging one to three sales a day to begin with, doubling that to two to six isn’t going to stand out much in the graphs. You have total things up for a few weeks before and after you start the ads to see the effect.

It takes time, all the while you’re spending $5-$10 each day and not seeing the graph spike like you want it to. It feels like you’re throwing money away, but getting data takes time.

With these numbers, you’re measuring the effectiveness of two things: 1) your ad’s ability to get someone to click on it (CTR); 2) the accuracy of your audience targeting (conversion).

If the first one’s bad then no one clicks. Second one’s bad and the customer says: “Oh, that looks cool! <click> WTF? A book? I don’t read … thought it was a movie! To hell with that.”

You can’t even get some affiliate income out of their next Amazon purchase because you can’t put affiliate links in Facebook ads. 🙁

But once you’ve collected the data about click-through and made the best educated guess about sales you can start to extrapolate things. Then you can decide how much revenue you want to target after the ads are paid for — and from that get how much your ad spend should be to achieve it.

So in the case above, the read-through’s worth $11.12 and to clear $5000 after paying for the ads we’d have to spend $2700 on the ads — close to $100 a day for a month.

You can download the spreadsheet and run your own numbers with the books in your series — it’ll automatically take into account the change to 35% royalty if you’re, say, selling your first book for $0.99 as a loss-leader.

If you’re interested in exploring Facebook ads for your books but don’t want to deal with the day-to-day management, such as reviewing and hiding comments, we can run ads for your books under the Indies Press or Darkspace Press pages, as well as assist with creatives. See the Author Services page for more information.

A note about Kindle Unlimited

KU screws everything up, as usual.

KU doesn’t tell you the number of people who borrow your book or how far they read — only the total page reads.

How you deal with KU borrows and reads in your calculations is up to you, but here’s what I do and why.

KU income is consistently 60% of my income and what I make from a KU full read through is roughly what I make from a sale.

So, in general, I assume that for every tracked sale I get there’s a corresponding KU borrow and a number of page reads that bring in the same dollar amount.

I.e. if Amazon says I had four sales on the day, I assume their were also four borrows who’ll, on average, read the whole book and earn me a corresponding amount. So I simply double the sales Amazon reports to take the impact of KU into account.

Maybe there are really twice as many borrows as sales but half of the KU readers bail in the first chapter, but whatever — the important part is the money and the money says it’s pretty much one-to-one.