Your cart is currently empty!

Category: taxes

-

Business of Writing: Hobby vs. Business – Why is it important?

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Is your writing career a hobby or a business? And why does it matter?

Well, it matters to the IRS — at least at the start of your career or when your income drops — and it should matter to you. Unless you’re at the stage of your writing career where you generally show a profit — in which case, this doesn’t matter to you, because you’re clearly a business and have already proven it. This is more for those writers at the start of their career, where they may put more money into covers, editing, etc. than there is income. Also not applicable if you’re incorporated, because then you are, by definition, a business entity.

There are basically three “states”, if you will, a business can be in, so far as the IRS is concerned:

Profit — which is where your income is greater than your expenses and you pay taxes on the difference. This is where we want to be, obviously.

Loss — which is where your expenses are greater than income.

Startup — which represents all of your expenses prior to being “open for business”.

The Hobby vs. Business question has to do with that second state — showing a loss for the year.

It’s normal for some businesses to have losses in the first year or years of operation. Your author business is no different. If your series doesn’t take off until the third book, and you’re writing one book a year, then your first two or three years could operate at a loss as you put money into covers, editing, and advertising, as well as maybe going to writing conferences and conventions to improve your craft and promote your work.

What happens with those losses is the Hobby vs. Business question.

If your writing is a hobby, meaning that you’re not running it as a business or trying to make a profit, then you eat those losses. You can only deduct expenses up to the amount of your income for Hobby losses. Make a $1000 but spend $1500 on editing and covers? You can only deduct that $1000.

On the other hand, if you suffer a loss in a year and your writing is a business, then that loss can offset your day-job salary income and you pay less in taxes on that.

How do you show that your writing is a business and not a hobby? By treating it like one — and, first, not saying things like “I just do it for fun” or “I’m happy if it pays for dinner once in a while” — but basically by showing that you’re trying to make a profit, even if you haven’t done so yet.

- Keep your business and personal money separate. Separate bank and credit accounts. These don’t have to be “business” accounts, but can be personal accounts you only use for business. If you’re putting salary income in to pay for editing or such, then transfer it to the “business” account and pay the editor from there. Same if you’re buying something personal with your royalty income — transfer it to the “personal” account and buy it with that card.

- Keep good records of your income and expenses. I like Quickbooks Self Employed for this and recommend it highly.

- Time and effort. Track how much time you spend on writing, marketing, and improving your craft.

- Have you tried different things to make a profit? I.E. changing up your advertising or writing in new markets because they might be more profitable.

- Were the losses during the startup phase of the business? I.E. Before you publish your first book?

- Do you have the knowledge to be successful? Such as improving your writing, but also improving your business skills? (Did you write down somewhere that you spent time reading this series of posts to accomplish that?)

Basically, you have to be able to argue and show evidence that you take your career as an author seriously, and are taking steps to achieve profitability.

Like too much of the US tax code, though, it is subjective, so do everything you can to document that you’re treating your writing like the business it is, and not just a hobby.

Now, that third state, Startup, defines the time before your book is for sale — before you’re “open for business” — and for a regular business, those startup costs would have to be capitalized (meaning the amount is deducted over a number of years). Some tax professionals say this applies to writers, but the IRS appears to say differently.

But once you’ve published something and put it up for sale (or sold something, if you’re going the traditional route), it could be argued that you’re “open for business” forever thereafter as a writer and don’t have to worry about this — you just make a profit or loss in any given year. Before that? I think it could go either way, but I lean toward the “expenses” rather than “startup costs” camp, because of this exemption.

There’s also the question of how this applies to the traditional publishing market. Are you “open for business” when the public can buy your book or when a publisher can? Does the act of shopping your manuscript or sending a query letter open you for business and end the startup costs question — if it even applies to writers?

I don’t know and you might want to query more than one tax professional — preferably those who have dealt with it before, so you’re not getting someone’s first opinion. For me, I went the expenses route, but I published within the first year, so didn’t have the multi-year question to deal with.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Do you have to send 1099s to your editor, cover artist, etc.?

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

I see more conflicting advice about 1099s every year than anything else. As an author, you’re going to get 1099 forms from those who’ve sent you royalties or other payments, but do you need to send them to those you’ve paid, such as your editor, cover artist, or other authors you might have split boxset royalties with?

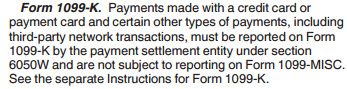

Several years ago, the IRS began requiring that 1099-MISC forms be sent to anyone paid more than $600 in a year, but then there was also the 1099K form sent by payment processors like credit card processors and PayPal. (Note: Royalties are different, see below.)

So … if you send the 1099MISC and PayPal sends the 1099K, then the poor editor winds up having to explain that, no, she didn’t receive the money twice. The rules were confusing, and still are, because the 1099K is only sent if more than $20,000 was paid … but how are you to know if your editor makes that much?

Many tax preparers have been saying to send the 1099MISC anyway and let the contractor sort it out … which is a pain.

In addition, in order to send the 1099MISC you also need the contractor to fill out a W9 with their social security number and keep that form for four years. (https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/forms-and-associated-taxes-for-independent-contractors)

For the record, it’s probably a bad idea to be sending W9s with SSNs through email, or, if you have already, leaving them sit around in your email history.

Anyway …

The current 1099MISC instructions are a little clearer:

This makes it clearer to me, at least, than past years, because the 1099MISC instructions don’t mention the 1099K’s reporting threshold. The wording “Payments made with … are not [emphasis added] subject to reporting on Form 1099-MISC” settles it, in my opinion.

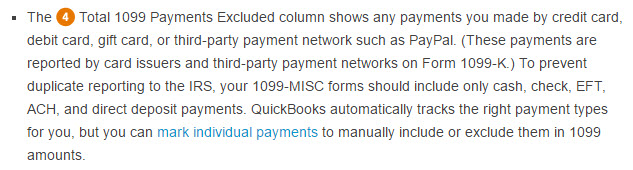

In addition, Intuit’s Quickbooks explicitly excludes payments made through these processors from the 1099s Quickbooks generates:

For these reasons, I don’t collect W9s or send 1099MISC forms to contractors I pay with credit card or PayPal or through other payment networks. If I pay via cash or check or ACH I do. I’ve also heard rumblings that there are IRS penalties for overreporting 1099 income to a contractor — which you’d sort of be doing if the contractor was also getting a 1099K for the income. Sort of a damned-do/damned-don’t situation.

Here are a couple other resources that seem to support my decision not to send 1099s to those I paid through a payment processor:

http://www.basi-usa.com/basi/1099-misc-reporting-with-quickbooks/

The corollary of this, of course, is that you also do work as an editor or artist, you might receive 1099MISC forms from those you did work for, but those funds might then have been reported twice, and you’ll have to document that. It might result in your having to explain it to the IRS, but that’s better than paying taxes twice.

Royalties

Royalties you pay to other authors, either a coauthor or authors in a boxset you organized, may be different.

These are not part of the $600-rule, but rather the $10 royalty rule. Either way, it’s the same 1099MISC, and the “payment processor”/1099K rule might also apply to this — but it’s possibly different. I tend to think that it is the same, given the placement of the 1099K instruction on the 1099MISC instructions — it appears to be general, regardless of the purpose of the 1099MISC (i.e. it applies to all uses of the 1099MISC, meaning do not file one if you use a payment processor).

Consulting a Tax Professional

If you do consult a tax professional on this issue, you should explicitly explain the method of payment and ask their opinion on the current 1099-MISC instructions, as well as pointing them to the Intuit link above. There are changes to the tax code every year, and they can’t always keep up with small changes in wording that might significantly change their interpretation.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]