Your cart is currently empty!

Author: sutherland

-

Book Recommendation: Star Realms: Rescue Run

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”1_4″][et_pb_image admin_label=”Image” src=”https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/61g1eSH%2BAEL.jpg” show_in_lightbox=”off” url=”http://amzn.to/2rc5vyT” url_new_window=”off” use_overlay=”off” animation=”left” sticky=”off” align=”left” force_fullwidth=”off” always_center_on_mobile=”on” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” /][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”3_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Since being court-martialed by the Star Empire, smuggler and thief Joan Shengtu has done what she needed to do in order to survive—gaining a reputation along the way. When a new client’s mission goes sideways, Joan finds herself caught in the middle of dueling gambits between the Star Empire and the Trade Federation. Recruited to perform the heist of a lifetime, the fate of the Star Empire rests in her hands.

On the opposite side of the galaxy, Regency BioTech manager Dario Anazao sees an unsustainable situation brewing that promises a full-scale revolution. The megacorporations of the Trade Federation have kept the population in horrible working conditions, violating their human rights. With no one else to help, Dario must take it upon himself to rescue the workers of Mars.

Can two heroes from warring factions come together to make a difference in the galaxy?

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Book Recommendation: The Sculpted Ship

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Starship engineer Anailu Xindar dreamed of owning her own ship, but she didn’t find the courage to actually go for it until she was forced out of her safe, comfortable job. She goes shopping for a cheap, practical freighter, but she ends up buying a rare, beautiful, but crippled luxury ship. Getting it into space will take more than her technical skills. She’ll have to go way outside her comfort zone to brave the dangers of safaris, formal dinners, a rude professor, and worst of all, a fashion designer. She may even have to make some friends… and enemies.

I saw The Sculpted Ship in the new releases a couple months ago and passed it by – the cover didn’t really appeal to me, though the description sort of did. Then I saw it again on Nathan Lowell’s Peer Reviewed and decided to check it out.

I found myself in agreement with Lowell’s evaluation — there are some issues. I would have liked to have seen a lot more of the story, rather than be told about it, and there’s a bit of deus ex machina in the end.

But, that being said, it’s a solid start — what appears to be a first book — and an enjoyable story. I look forward to seeing it continue and, though it’s not in Kindle Unlimited, the $2.99 price tag makes it a low risk to check out.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Preorders

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals. Also, I live in the US, so am really only speaking to US law and the US tax code.

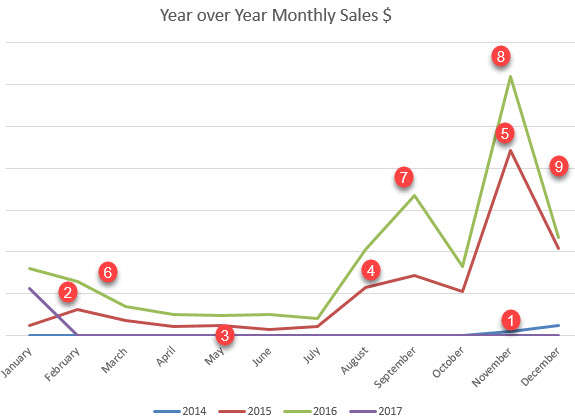

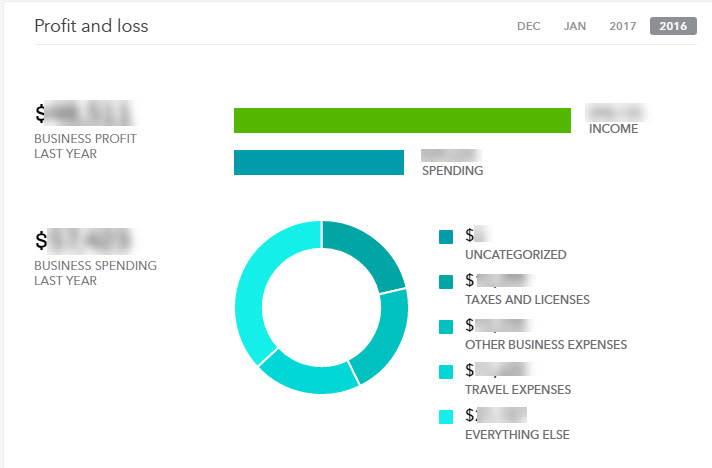

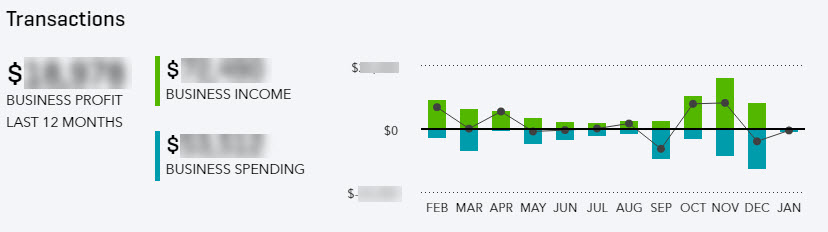

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”] Presale periods are a surprisingly divisive issue for authors, with some swearing by them and others … well, there’s some swearing involved there, as well. One of the arguments against them is that, at least on Amazon, sales from the prerelease period don’t “count” toward rank on release day, thus not driving a new release as high in the charts as it might otherwise go. I think that’s short-sighted. Marketing is all about eyeballs – getting more eyeballs on a product, repeatedly, so that it becomes more familiar and more likely to be purchased. Given this, it would seem that sustained, longer-term visibility is more beneficial than a shorter period, even if the shorter period gets more individual eyeballs. And that latter, that a higher rank for a shorter time gets more eyeballs than a lower rank for a longer time is debatable. I’d wager, were I a betting man, that its the opposite — that multiple months in a genres Hot New Release list is more valuable in terms of eyeballs than a week, or even a month, in Amazon’s top 100. A presale period does this by staying on the new release charts longer, exposing the book to eyeballs more often, and my personal dataset seems to bear this out. First by happenstance, then by design, I released three of my four books following the same pattern and at the same time of year. In addition, I do very little marketing, so my sales charts are largely unaffected by ads and are driven almost exclusively by visibility on Amazon. My first, third, and fourth books were all made available for prerelease in August, starting in 2014, with a release date in November, the maximum prerelease period available on Amazon to a self-published author. There were relatively few presales with the first book, but what I observed with the third and fourth was striking. Now, all of the expected YMMV caveats apply – this is data for a series, in the space opera genre, and may not apply elsewhere, especially to stand alone novels. Also, I’m tracking dollars-earned, not number of copies, because, frankly, that’s what I care about.

- I put my first book on presale in August 2014 for a November release. It had a trickle of presales over that time, and more sales when it finally released.

- Book 2 went on presale in November 2014 for a February release, which, I think, helped Book 1’s sales after a bit.

- After which, sales fell steadily through the new in the last 30-, 60-, and 90-day lists.

- Until Book 3 went on presale in August 2015. Now, it’s important to remember that the dollars for presales don’t register until the book’s actually released, so this jump in sales (of 10x the previous months) is entirely sales of the existing books, not the new one. I did virtually no advertising or promotion during this time, so the effect is entirely attributable to the visibility of Book 3 on the Hot New Release charts, which are significantly easier to get on than a category’s Best Seller chart.

- So I got 90-days of that visibility, then all the revenue from presales, and still had 30-days of “new release” status going into November.

- The question I started asking as Book 3 lost that status was: Is that repeatable? Not just the spike of new release sales and initial visibility, but the sustained sales of the previous books while the next is in prerelease? It seemed logical, but so many authors were swearing that the Day One spike was essential.

- Well, sure enough, it did repeat, with slightly different pattern because Book 4 went on prerelease a bit later in August this time.

- All of which resulted in, again, more presales of the next book, making November 2016 my best month ever.

- And projecting December to be better than last year as well, though not as much as it could be because the audiobook of the new release is a bit delayed (Book 3’s audiobook released in December 2015, increasing that month’s revenue.

It could be argued that the higher rank of a Day One, no-prerelease spike might make more money, but given what I know about marketing, I don’t think so. Amazon’s algorithms favor stability of rank over spikes, so I don’t think a higher spike would last as long in its effect. I know that it would take a huge number of sales in 30-days of visibility from no prerelease to make up for the revenue I see in 120-days with one – it doesn’t seem feasible. Marketing is about eyeballs and while some people will buy your book the first time they see it, others will think “maybe” – the longer it’s visible, the more opportunities there are to both get the initial buyers and convert the “maybes” to yeses. I know I plan to repeat this with my next release and hope 2017 will be better still. As you plan your own prerelease, keep in mind that you can shorten it, but not lengthen it. So you can put your book up for a 90-day prerelease, then watch its sales and the sales of your other books. If it turns out that sales of your other books don’t go up, or go up and then fall, or your new book doesn’t make the Hot New Release chart for your genre and stay there, you can always bring the release date forward and have it release early. If yours does follow the above pattern, though, you can maximize its effect on visibility. [/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Whether to Incorporate

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals. Also, I live in the US, so am really only speaking to US law and the US tax code.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

The short answer, for most authors, is don’t. It provides little or no benefit with increased expense and complexity.

The longer answer is maybe, and depends on your specific circumstances — the decision also requires maths, so there’s that.

Let’s look at the most typical options you have for running your author business.

Sole Proprietorship

This is likely where you’re at now if you’re reading this. It’s just you, doing business as yourself. You might have filed a DBA (Doing Business As) for your state, but that doesn’t change that it’s you, personally, doing business.

In this method, you file a Schedule C form with your 1040 and the profit from your business is added to your personal income. You pay personal income tax on it, as well as “self-employment” tax, which is just the portion of Social Security and Medicare that an employer would typically pay “on your behalf”.

As an aside, do not assume that the “self-employment” tax is some sort of penalty you’re paying for being self-employed in your own business. Just because an employer “pays” it, doesn’t mean that it doesn’t come out of the workers’ checks. To an employer, it’s still a cost of having that employee — whether that 8%-or-so is paid to the employee or to the IRS makes zero difference to the employer so far as the costs go. If they weren’t paying it to the government directly, it would likely result in increased wages due to market forces.

Regardless, that’s Sole Proprietorship — it’s simple, easy, and the default state of your author business. There’s nothing you need to do to set it up or continue in that state.

LLC

The next step up the business chain is the LLC, or Limited Liability Corporation. It is a separate legal entity from you — something people sometimes have trouble wrapping their heads around. So far as the law is concerned, the LLC becomes something that can own property and will outlive you.

If you set it up this way, or anything other than sole proprietorship, you’ll be selling the rights to your books to the LLC, then you’ll own shares (typically 100% for an author) of the LLC, and make decisions as an officer of the LLC.

In this instance, for tax purposes, you’ll still be filing Schedule C with your 1040 and the business profit will flow through to your personal income, where you’ll be taxed at that rate and pay the “self-employment” tax. There are no tax benefits to an LLC for a single-owner author, and there are some small startup costs and ongoing paperwork and expenses.

It might run you a few hundred dollars if you have an attorney set up the LLC for you, less if you do it yourself, then there’s usually an annual charge from your state and some paperwork to file. It’s not complicated or expensive, but it is moreso than a sole proprietorship.

The two main benefits of an LLC do not typically apply to authors. These are partnership and liability.

An LLC allows you to divvy up the shares of the business amongst several people — but that’s not something you’re likely to do as an author.

The main benefit of an LLC is limited liability (it’s right there in the name), which means someone could sue the business, but the business owner’s private assets are protected. Meaning they can get the store but not the owner’s house.

The thing is … you’re not running a lawn service company. You have no employee who might drive a riding lawn mower over a five-year old. Your writing is, in fact, unlikely to kill toddlers …

Unless you’re writing Fun Games with Sharp Objects for Five-year Olds, but even then the limited liability isn’t going to help you because you’re an author — if you get sued, it will be for something you wrote, whether you defame someone or the toddler plays Your Towel-Cape is Magic – You can Fly!

Either way, they’re going to sue you, personally, as well as the company, and that corporate veil will go up faster than the curtains in Who Can Find the Most Things that Burn?

The one area in which an LLC is beneficial to an author is in death. Yes, you’re going to die one day, but you’re creating an asset which will live beyond you and may provide royalties to your heirs for decades after you’re gone — those assets will also cause innumerable headaches for your estate’s executor and possibly your heirs unless you take steps to ease the transition. An LLC can do that by providing a smooth transfer of ownership in the rights to your books, as well as obviating the need to change your personal accounts to someone else’s.

I’ll get into estate planning in more depth in a later post, but for now just know that this is really the only benefit an LLC provides to an author.

Except that you can elect to have an LLC treated as an S Corp by the IRS. It’s an option, and gives you the tax benefits of the S Corp (below) with the simplified annual paperwork requirements of the LLC. So that hybrid is likely the direction I’ll go when it’s time.

Incorporation (S Corp)

There can be a tax advantage to Incorporating, but it’s so dependent on your individual circumstances (your book income, any other income, your spouse’s income, etc.) that it’s impossible to make the decision without running the numbers — i.e. doing your taxes as though you were a sole proprietorship, then doing them again as a corporation and comparing the results. This is why I recommend consulting a professional if you’re considering it.

In general, it’s not something you should consider or worry about until you’re making six figures from your book income. If you typically end the year having spent all of your book income on either writing expenses or personal expenses. It’s only if you have money left over, quite a bit of it, that a corporation begins to make sense.

This is because the primary advantage of a corporation has to do with taxes. Basically, you can pay yourself a salary and leave excess profits in the business or take them as dividends/distributions — your salary is taxed personally, along with SS and Medicare taxes, but the profits you leave in the business are taxed separately at the, possibly, lower corporate rate or the even lower dividend rate.

Don’t think you can just take it all as a dividend, though, because the IRS does say you have to pay yourself a “fair” salary out of the corporation. What “fair” is … well, that’s not defined. It should be the equivalent of what salary you’d earn doing that job for an employer on the open market, in theory … but how does that apply to an author?

But you might be opening yourself up to state corporate taxes as well, especially if you live in a state with no personal income taxes. And your salary has to be “reasonable” to keep you from making it too low or too high based on the work. And there are host of other what-ifs that might impact the decision.

Bottom Line

So if you’re making more than six figures and typically have money left over every year, you might want to consult a tax professional about incorporating. Other than that, Sole Proprietor is probably good for, unless you’d like to make things simpler for your heirs, in which case consider an LLC.

[Edited May 2017]

As if it weren’t already complicated enough, President Trump’s proposed tax plan (one of them, anyway), impacts this decision. It’s been proposed to lower the corporate rate to 15% but also allow sole proprietors and LLCs to elect that corporate rate. This appears to be in lieu of rolling the profit over to earned income and paying SS & Medicare taxes on it. So for 2017, there might be a wait-and-see attitude that’s best. Talk to a qualified tax professional about your situation, but also bring up this possibility as they might not be aware of it.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Picking a Tax Professional

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals. Also, I live in the US, so am really only speaking to US law and the US tax code.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This will be a short post, but an important one. Picking the right tax professional can save you or cost you — a lot of money.

First thing to remember is that “tax professional” does not, necessarily, mean Accountant or CPA. Not all accountants understand taxes or do them regularly. You’re looking for a tax preparer — someone who knows the tax code inside and out, at least the parts that apply to your author small business.

You may find, depending on the size of your author business, that you want or need an accountant for other business matters. Who you choose for that may or may not be the same as your tax preparer. Finding both in one, assuming you need an accountant, is good, obviously, but here we’re going to talk only about the tax aspects.

The second thing to remember is that your taxes are different now than an individual’s. You have a business. Finding a tax professional for your business does not mean dropping a paper bag of receipts in the lap of whatever dude happens to be behind the desk at Walmart this tax season.

This is not a one-off, prepare the return and done thing. As a business owner, you should be creating an ongoing, multiyear relationship with your tax professional. You want someone who will do your taxes every year and be able to make recommendations based on their knowledge of your business’ past as well as projections about its future. This is because some tax decisions, which might save you a significant amount of money, have to be made at the beginning of the tax year.

So, you are looking for:

- A tax professional. Someone who understands and works with the tax code as their primary job.

- Moreover, a small business tax professional, not someone who specializes in personal taxes — neither are you interested in a specialist in big corporations.

- Preferably, and hardest, someone who does taxes for other authors, so they know the writing business.

- Someone you can work with for years, and throughout the year — so you can make an appointment and talk to them in August if there’s some significant change in your business.

If you’re a part of a local writer’s group, ask around of the more successful writer’s. They may have someone who meets the criteria.

You can also locate a tax professional through either National Association of Enrolled Agents or National Association of Tax Professionals.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Hobby vs. Business – Why is it important?

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

Is your writing career a hobby or a business? And why does it matter?

Well, it matters to the IRS — at least at the start of your career or when your income drops — and it should matter to you. Unless you’re at the stage of your writing career where you generally show a profit — in which case, this doesn’t matter to you, because you’re clearly a business and have already proven it. This is more for those writers at the start of their career, where they may put more money into covers, editing, etc. than there is income. Also not applicable if you’re incorporated, because then you are, by definition, a business entity.

There are basically three “states”, if you will, a business can be in, so far as the IRS is concerned:

Profit — which is where your income is greater than your expenses and you pay taxes on the difference. This is where we want to be, obviously.

Loss — which is where your expenses are greater than income.

Startup — which represents all of your expenses prior to being “open for business”.

The Hobby vs. Business question has to do with that second state — showing a loss for the year.

It’s normal for some businesses to have losses in the first year or years of operation. Your author business is no different. If your series doesn’t take off until the third book, and you’re writing one book a year, then your first two or three years could operate at a loss as you put money into covers, editing, and advertising, as well as maybe going to writing conferences and conventions to improve your craft and promote your work.

What happens with those losses is the Hobby vs. Business question.

If your writing is a hobby, meaning that you’re not running it as a business or trying to make a profit, then you eat those losses. You can only deduct expenses up to the amount of your income for Hobby losses. Make a $1000 but spend $1500 on editing and covers? You can only deduct that $1000.

On the other hand, if you suffer a loss in a year and your writing is a business, then that loss can offset your day-job salary income and you pay less in taxes on that.

How do you show that your writing is a business and not a hobby? By treating it like one — and, first, not saying things like “I just do it for fun” or “I’m happy if it pays for dinner once in a while” — but basically by showing that you’re trying to make a profit, even if you haven’t done so yet.

- Keep your business and personal money separate. Separate bank and credit accounts. These don’t have to be “business” accounts, but can be personal accounts you only use for business. If you’re putting salary income in to pay for editing or such, then transfer it to the “business” account and pay the editor from there. Same if you’re buying something personal with your royalty income — transfer it to the “personal” account and buy it with that card.

- Keep good records of your income and expenses. I like Quickbooks Self Employed for this and recommend it highly.

- Time and effort. Track how much time you spend on writing, marketing, and improving your craft.

- Have you tried different things to make a profit? I.E. changing up your advertising or writing in new markets because they might be more profitable.

- Were the losses during the startup phase of the business? I.E. Before you publish your first book?

- Do you have the knowledge to be successful? Such as improving your writing, but also improving your business skills? (Did you write down somewhere that you spent time reading this series of posts to accomplish that?)

Basically, you have to be able to argue and show evidence that you take your career as an author seriously, and are taking steps to achieve profitability.

Like too much of the US tax code, though, it is subjective, so do everything you can to document that you’re treating your writing like the business it is, and not just a hobby.

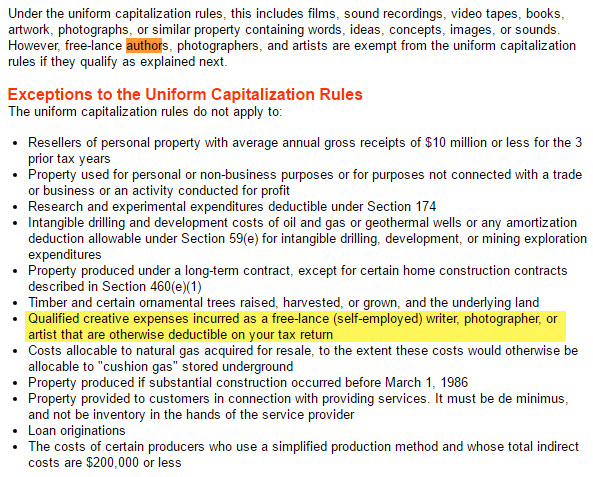

Now, that third state, Startup, defines the time before your book is for sale — before you’re “open for business” — and for a regular business, those startup costs would have to be capitalized (meaning the amount is deducted over a number of years). Some tax professionals say this applies to writers, but the IRS appears to say differently.

But once you’ve published something and put it up for sale (or sold something, if you’re going the traditional route), it could be argued that you’re “open for business” forever thereafter as a writer and don’t have to worry about this — you just make a profit or loss in any given year. Before that? I think it could go either way, but I lean toward the “expenses” rather than “startup costs” camp, because of this exemption.

There’s also the question of how this applies to the traditional publishing market. Are you “open for business” when the public can buy your book or when a publisher can? Does the act of shopping your manuscript or sending a query letter open you for business and end the startup costs question — if it even applies to writers?

I don’t know and you might want to query more than one tax professional — preferably those who have dealt with it before, so you’re not getting someone’s first opinion. For me, I went the expenses route, but I published within the first year, so didn’t have the multi-year question to deal with.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Do you have to send 1099s to your editor, cover artist, etc.?

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ saved_tabs=”all” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series. As part of this series, I discuss law and taxes, so it’s important for you to remember that I’m neither a lawyer nor a tax professional. This is not advice — it’s my understanding and, in many cases, what I do and why. You should take this as the base to develop your own knowledge and understanding, or consult the appropriate professionals.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

I see more conflicting advice about 1099s every year than anything else. As an author, you’re going to get 1099 forms from those who’ve sent you royalties or other payments, but do you need to send them to those you’ve paid, such as your editor, cover artist, or other authors you might have split boxset royalties with?

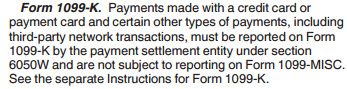

Several years ago, the IRS began requiring that 1099-MISC forms be sent to anyone paid more than $600 in a year, but then there was also the 1099K form sent by payment processors like credit card processors and PayPal. (Note: Royalties are different, see below.)

So … if you send the 1099MISC and PayPal sends the 1099K, then the poor editor winds up having to explain that, no, she didn’t receive the money twice. The rules were confusing, and still are, because the 1099K is only sent if more than $20,000 was paid … but how are you to know if your editor makes that much?

Many tax preparers have been saying to send the 1099MISC anyway and let the contractor sort it out … which is a pain.

In addition, in order to send the 1099MISC you also need the contractor to fill out a W9 with their social security number and keep that form for four years. (https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/forms-and-associated-taxes-for-independent-contractors)

For the record, it’s probably a bad idea to be sending W9s with SSNs through email, or, if you have already, leaving them sit around in your email history.

Anyway …

The current 1099MISC instructions are a little clearer:

This makes it clearer to me, at least, than past years, because the 1099MISC instructions don’t mention the 1099K’s reporting threshold. The wording “Payments made with … are not [emphasis added] subject to reporting on Form 1099-MISC” settles it, in my opinion.

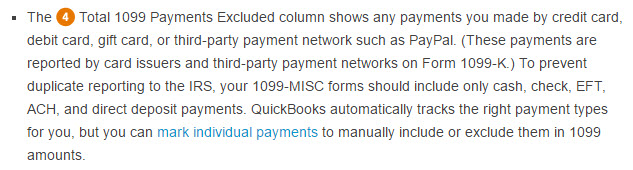

In addition, Intuit’s Quickbooks explicitly excludes payments made through these processors from the 1099s Quickbooks generates:

For these reasons, I don’t collect W9s or send 1099MISC forms to contractors I pay with credit card or PayPal or through other payment networks. If I pay via cash or check or ACH I do. I’ve also heard rumblings that there are IRS penalties for overreporting 1099 income to a contractor — which you’d sort of be doing if the contractor was also getting a 1099K for the income. Sort of a damned-do/damned-don’t situation.

Here are a couple other resources that seem to support my decision not to send 1099s to those I paid through a payment processor:

http://www.basi-usa.com/basi/1099-misc-reporting-with-quickbooks/

The corollary of this, of course, is that you also do work as an editor or artist, you might receive 1099MISC forms from those you did work for, but those funds might then have been reported twice, and you’ll have to document that. It might result in your having to explain it to the IRS, but that’s better than paying taxes twice.

Royalties

Royalties you pay to other authors, either a coauthor or authors in a boxset you organized, may be different.

These are not part of the $600-rule, but rather the $10 royalty rule. Either way, it’s the same 1099MISC, and the “payment processor”/1099K rule might also apply to this — but it’s possibly different. I tend to think that it is the same, given the placement of the 1099K instruction on the 1099MISC instructions — it appears to be general, regardless of the purpose of the 1099MISC (i.e. it applies to all uses of the 1099MISC, meaning do not file one if you use a payment processor).

Consulting a Tax Professional

If you do consult a tax professional on this issue, you should explicitly explain the method of payment and ask their opinion on the current 1099-MISC instructions, as well as pointing them to the Intuit link above. There are changes to the tax code every year, and they can’t always keep up with small changes in wording that might significantly change their interpretation.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Quickbooks Self Employed

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” saved_tabs=”all” global_module=”5451″]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

I’m going to be talking about Quickbooks Self Employed (QBSE) a lot in the series of posts on taxes, so figured it would be useful to have a full review post of it. Quickbooks has multiple offerings, so it’s important to understand that I use and recommend the Self Employed product, and this review isn’t of the Online or Desktop offerings. Those are good products too, I’m sure, but I think they’re overpowered for use by the typical author.

I’ve been using QBSE for a year now and love it. It’s easy, powerful, and saves me a lot of time — it’s also economical, at only $10/month ($17 if you want to include TurboTax Home & Business for filing your taxes, which I do).

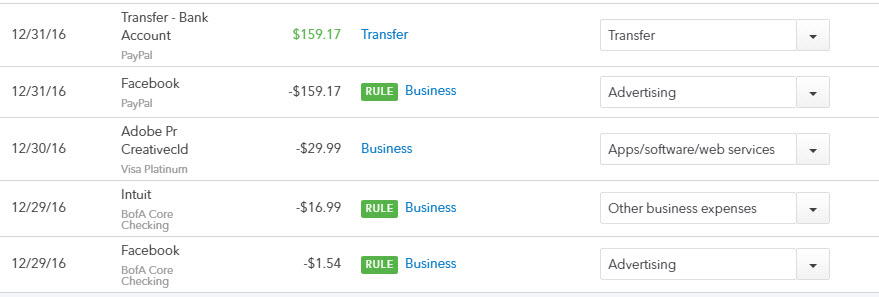

The first thing you do with QBSE is connect it to your business bank and credit card accounts, as well as PayPal, so it can automatically read in the transactions. This gives you a single register of all your business transactions, and as new transactions appear, you have the ability to label them as Business or Personal with a single click. You also categorize the business items based on Schedule C categories for taxes, and QBSE lets you set up rules to do this automatically. For instance, all payments to Facebook can be set as Business and Advertising automatically.

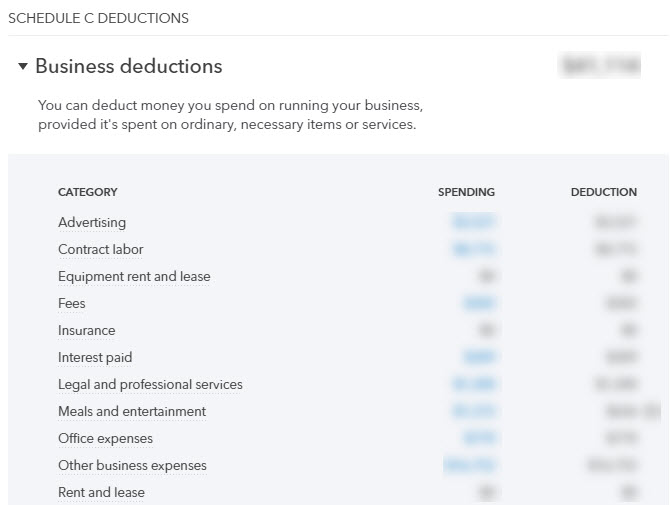

All of those get totaled up into their categories at the end of the year so you can print them out for your tax professional or they transfer directly to TurboTax if you use that.

This, in and of itself, is worth the price, in my opinion, but QBSE does a lot more.

It constantly calculates your estimated taxes throughout the year, telling you at any time what your quarterly payments should be. In doing this, it takes into account your income and expenses from the previous year (once you’ve been using it long enough) and, very useful, it takes into account your day job income and withholding — so its calculations of estimated tax accurately take into account the tax bracket that your writing income falls into.

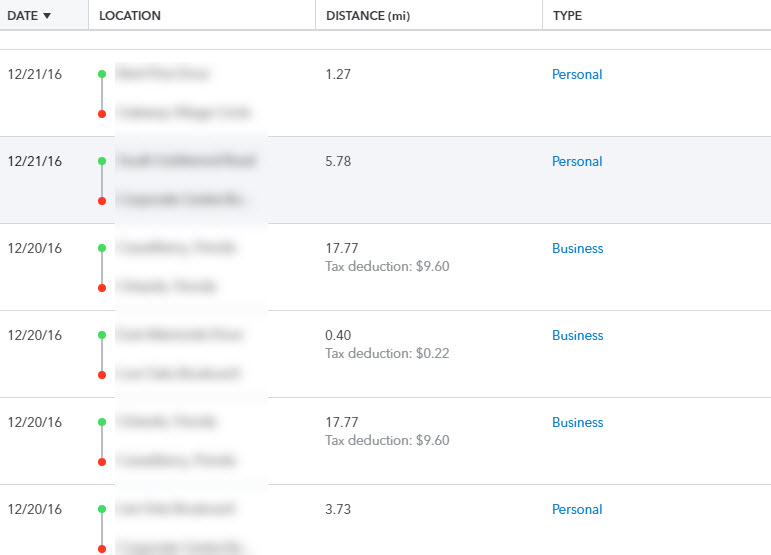

The next feature that I make use of is the mileage tracker in the QBSE mobile app. This tracks your driving and lets you label each trip as business or personal. If you make a lot of trips to cons or events, it’s a huge convenience. You just periodically open the app, then swipe right for Personal or left for Business on each trip. At the end of the year, you get the total business mileage and deduction, as well as a spreadsheet of all the trips documented for tax purposes.

If you have an accountant or tax professional, they might use Quickbooks products as well, and QBSE allows you to share your information with them directly online. And, if you do any editing or cover designs in addition to writing, you can send invoices directly from within the application.

And it’s kind of fun to watch the dashboards update you on your business every time you open the app.

Overall, Quickbooks Self Employed is a huge timesaver and makes for more accurate records. I highly recommend it.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

-

Business of Writing: Estimated Taxes

[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”row”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” global_module=”5451″ background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” saved_tabs=”all”]

This post is part of my Business of Writing series.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

In the last post, I examined why taxes seem to surprise so many authors whose books become moderately successful for the first time. In this one, we’re going to talk about the Estimated Tax requirement.

This is mostly for new authors or those who are just now hitting some level of success – say a few hundred or a thousand dollars a month (profit) or a first traditional contract of several thousand. After the first year of that, and getting bit by the penalty for not paying estimated taxes, most get it figured out.

Here’s what the IRS has to say about it: https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes

The IRS recommends you use their multipage worksheet (https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1040es.pdf), which involves estimating your income and deductions, both personal and business – and, since writing is a pretty variable business, you should do that worksheet for each quarterly estimated tax payment …

Which is sort of like having to do you taxes five times a year, in my opinion.

This is why I use a tool, which I’ll pitch up front, to do most of that for me.

I use Quickbooks Self-Employed (http://fbuy.me/d2DLB) and recommend it to anyone making enough for this to be a complicated issue. At $10/month, it’s worth it.

Quickbooks SE (and the version is important, they have, like, seven versions available, Self-Employed being a less-expensive and easier version to use), aside from all its other features, calculates your quarterly tax payments for you based on your real income and expenses. It also takes into account your day-job income, so knows what bracket your author earnings will fall into – and it’s real time.

That means it will calculate and recalculate right up until the quarterly deadline based on your real numbers.

There’s a lot else it does, and I’m going to recommend it several times during this series.

A quick method of dealing with estimated taxes that doesn’t cost a monthly fee for a tool is to just pick a percentage — 30% or 40%, depending on what bracket you fall in – and set that aside from all income, then just send it to the IRS quarterly. In this case, you’ll likely overpay, as you aren’t really tracking your profits and taking expenses into account, but you’ll get the extra back when you file your return.

I’m not a fan of giving the government interest-free loans, but you should make your own business decision about whether it’s worth the avoidance of time and energy spent on a more accurate quarterly calculation.

If you’re the sort who has difficulty with money laying about – such as wanting to “borrow” it for other things – then quarterly payments might not be for you. Even though the form from the IRS has quarterly vouchers, you can make estimated tax payments anytime if you do it online (https://www.irs.gov/payments). You specify the current tax year and that it’s an estimated payment, then send the money on your schedule. This is a good method if you want that money out of your accounts on a monthly basis, right after the royalties come in, so you’re not tempted.

“I can buy that 70-inch 4K TV now and just make up the taxes off next month’s royalties …”

So, yeah, if that idea would ever appeal to you, do the monthly payment thing. It works with Quickbooks SE too, you just have to do the math on what Quickbooks is calculating for the quarter, and it’s what I do.

If Quickbooks is saying I’ll have to send $3000 for the quarter and it’s the first month of the quarter, then I send $1000 as soon as my royalties for that month come in ($3000 / 3 months in the quarter). If the next month isn’t quite as good, then Quickbooks will recalculate it and track what I’ve paid. So the second month of the quarter might end with QB saying it’s now going to be $2000 for the quarter, and I then send in $500 ($2000 minus the $1000 I sent the previous month, so $1000 / 2 months left in the quarter).

It’s variable, but it works for me.

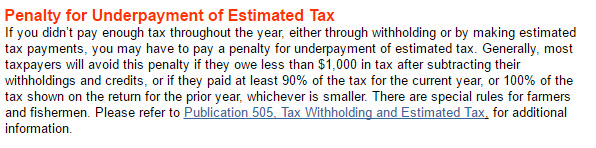

The important thing, whichever system or tool you use, is to make sure you’ve paid enough in estimated taxes to avoid the penalty.

Basically, you’re not allowed to owe them more than $1000 come tax day … they’re perfectly happy to owe you several thousand as your “refund”, though. Go figure.

Your first year of writing success will probably be safe from the penalty if you have a day job consistent with the previous year – this is because you’ll have paid roughly the same amount as last year in day-job withholding, which meets the “100% of the tax shown on the return for the prior year” requirement to avoid the penalty.

Your second year of success, though, won’t have this advantage because you’ll have that tax on book income that won’t have been covered by withholding – unless you typically receive a really large refund.

The bottom line:

At least four times a year you need to estimate your income and expenses then send a check to the IRS.

Use the IRS’s form (https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1040es.pdf) or get a tool like Quickbooks (http://fbuy.me/d2DLB) to make the calculations.

Make the payments monthly (https://www.irs.gov/payments) instead of quarterly if you have trouble with setting money aside for several months.

Next up will be a post on deductions (coming soon), and why you should be tracking your expenses even if you haven’t published your book yet.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]